Rising Tides: Is LA Ready for Sea-Level Rise?

Our South Bay town hall detailed how coastal cities can best protect themselves.

Remnants of a bluff-top apartment building in Pacifica that crumbled to the beach, where rocks form a barrier against the rising sea. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times).

The ocean is moving in. But unlike most unwanted guests, sea level rise is here to stay.

Because of the carbon emissions already emitted since the Industrial Revolution, sea level rise (SLR) is inevitable in our region. California’s oceans are expected to rise at least 3.5 feet by 2050, creating devastating impacts – from severe coastal flooding to widespread loss of cherished beaches. But that does not mean all hope is lost. With proper resilience planning at the state and local levels, our region can escape the most cataclysmic effects. But we need to start acting right now.

Tracy Quinn (left), Rosanna Xia (center), and Warren Ontiveros (right) in conversation at Heal the Bay’s Sea Level Rise panel in Hermosa Beach.

That was the stark assessment of panelists gathered Sunday, April 28, for Heal the Bay’s “Rising Tides” town hall at the Hermosa Beach Community Center. Heal the Bay CEO Tracy Quinn moderated a lively conversation with Rosanna Xia, L.A. Times coastal reporter, and Warren Ontiveros, chief planner for L.A. County’s Beach and Harbors division. Hermosa Beach Mayor Justin Massey welcomed the audience.

Xia, author of the acclaimed book “California Against the Sea: Visions for a Vanishing Coastline,” urged policymakers to reframe SLR as an opportunity rather than a disaster. California can mend its “fractured relationship with our shoreline,” she argued, by adopting the mindset of the region’s first settlers. The Chumash, guided by a spirit of balance and reciprocity, looked to care for and heal the shoreline rather than command and control it. Our state has seen rising and falling seas for millennia, Xia noted. Centuries ago, California’s northern Channel Islands formed a single land mass until the Pacific Ocean rose and created five separate islands. The coast is not static, it is always changing.

But today’s challenges are starker given human-made emissions. Melting polar ice caps and increased expansion of water through rising ocean temperatures are the primary SLR drivers.

And those rising tides could prove disastrous. California could lose nearly 70% of all beaches and all its wetlands by 2100 if we fail to act. That loss would truly be a doomsday scenario, with 70M annual day visits to beaches annually and $1.3 billion in economic stimulus from the coastal economy.

Ontiveros shared some of the steps the County is taking to build greater resilience to the SLR onslaught. His division has created a scorecard for identifying the two dozen LA County beaches most vulnerable to erosion, flooding, and lack of public access. According to the County, the 10 beaches most at risk, in order of vulnerability, are Zuma, Redondo Beach, Malibu Surfrider, Point Dume, Dockweiler, Dan Blocker, Las Tunas, Topanga, Nicholas Canyon, and Will Rogers.

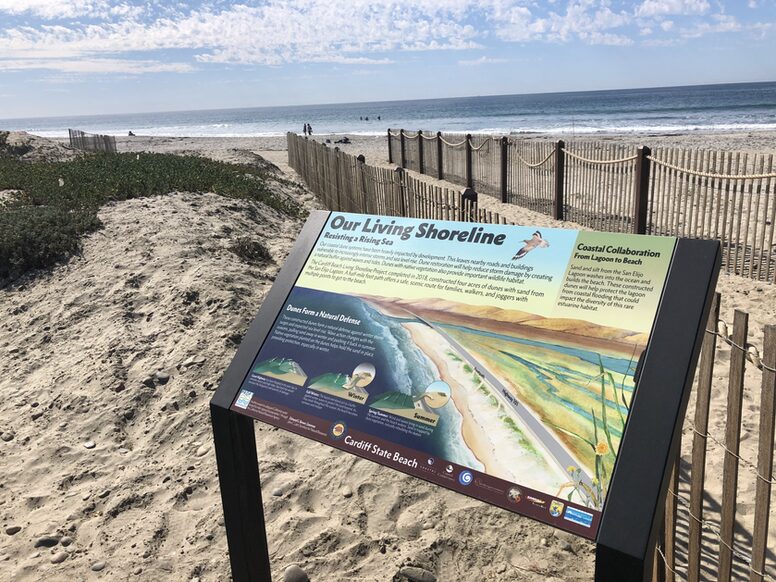

County engineers are readying several so-called beach nourishment projects to help preserve sand and public access in these threatened sites. In a hybrid mechanical-natural adaptation move, engineers hope to take tons of sand from the deep sea and “transplant” it on the Zuma and Point Dume shorelines. They would use the reclaimed sand to create “living shorelines,” where installed dunes and plant life would retain sand longer and provide natural buffers to flooding. The plans, which face many permitting and logistical challenges, would add 25 feet of sand to these iconic beaches.

Xia then encouraged the audience to think of the shoreline not so much as a place but as a process. Everything is always shifting, she said. Trying to fix straight lines and immovable objects on the shorelines is a fool’s errand.

The panelists agreed that buffering our coast and building resilience will require both engineered concrete solutions, such as relocating highways, and nature-based solutions, such as wetlands restoration, to accommodate increased flooding. Coastal residents will have to accept change. Their neighborhoods and the larger coastline will look different, panelists said.

Xia described a recent project in Sonoma County that saw Caltrans rebuild an arterial coastline highway that once snaked along Gleason Beach as an overpass further inland. Underneath the roadway, engineers designed a series of natural buffers and floodplains. Some residents called the new project an eyesore, Xia noted, while others saw it as a boon to a threatened community.

“The ‘my way or the highway’ mentality can’t work,” Xia said. Communities need to compromise and be realistic.

Ontiveros singled out the threatened Cardiff Beach in northern San Diego as an example of residents and planners working together to successfully adapt to rising seas. Nearly five acres of dune habitat have been restored in a multi-benefit project that will help protect a vulnerable section of PCH and increase public access to local beaches.

Xia noted that statewide resilience will be achieved through a series of iterative projects like Cardiff. There will not be one master document that solves all the many challenges in one fell swoop. Planning means envisioning and building continually over decades, where knowledge gained can be applied to the next challenge.

Panelists did not delve into the tricky question of how we find funds to pay for all this resilience work, which could hit $1 trillion statewide by the century’s end. Capitol lawmakers have made more federal funds available as part of a renewed push to protect the nation’s infrastructure.

While legislators and scientists have led the push to battle SLR, Xia urged decision-makers to widen the idea of who is an expert. Indigenous communities and frontline neighborhoods must be part of finding solutions, she said. Ontiveros echoed her comments, noting that millions of inland beachgoers depend on the sea for recreational and therapeutic relief. Hearing from inland communities is critical and will require proactive outreach, he said.

The session ended with thoughts on how everyday residents can best help their communities prepare for the ravages of sea-level rise. Coastal city residents should get involved in local city planning, Xia urged. By 2034, every beachside municipality must submit a Local Coastal Plan to state officials, with SLR vulnerability assessments and resilience recommendations.

To get a copy of Rosanna Xia’s book, please click here.